by Bob Pratico, submitted at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Mar 2023

Introduction

In the 680s a monk called John Bar Penkāyē was working on a summary of world history in his remote monastery by the swift-flowing River Tigris, in the mountains of what is now south-east Turkey. When he came to write about the history of his own times, he fell to musing about the Arab conquest of the Middle East, still within living memory. As he contemplated these dramatic events he was puzzled: ‘How’, he asked, ‘could naked men, riding without armour or shield, have been able to win . . . and bring low the proud spirit of the Persians?’ He was further struck that ‘only a short period passed before the entire world was handed over to the Arabs; they subdued all fortified cities, taking control from sea to sea, and from east to west-Egypt, and from Crete to Cappadocia, from Yemen to the Gates of Alan [in the Caucasus], Armenians, Syrians, Persians, Byzantines and Egyptians and all the areas in between . . .1

In 1991, David Aikman, Senior Correspondent for Time magazine, wrote that “Islam remains a very powerful, coherent religion, and its continued global vitality obviously impinges on the effectiveness of Christians who seek to make the faith of the gospel of Jesus Christ known at least equally well in all parts of the world”.2 It is formidable to uncover the history of early Islam with any certainty due to the sparse availability of reliable documents that were contemporaneous with its origins in the sixth and seventh centuries. David Waines, a degreed expert in Islamic studies, admits that it is unlikely we will ever know for sure “what really happened” in detail during the early years of Islam.3 Karl-Heinz Ohlig identifies the pertinent Muslim documents as the (1) the Sira of Ibn Hisham dating to 834, (2) a history of military campaigns by al-Waqidi dating to 822, (3) a book called “Classes” of “Generations” by Ibn Sa’d dating to 845, (4) a book called “Annals” by al-Tabari dating to 922, and (5) the six canonical collections of hadith dating to the late ninth century. Karl-Heinz Ohlig notes though, “following the canons of historical-critical research, these reports written approximately two hundred years after the fact, should be taken into consideration only with great reservations”.4 Ignaz Goldziher, considered one of the “fathers” of Islamic studies, warned in 1900 against drawing on the “abundant materials of Muslim tradition as the source for the clarification of the early years of Islam”.5 Ohlig cautions that Goldzhier’s warning from more than a century ago was not heeded and that the early history of Islam “was and is still interpreted back” from much later Muslim sources.6

Gabriel Reynolds acknowledges the problem that while these Muslim accounts might have an “authentic core”, it is “difficult to know where to find that authentic core since we do not have any ancient non-Muslim accounts of the Prophet’s life with enough detail to offer grounds for comparison”.7 The formative period of Islam is highly contested; a few scholars are so skeptical that they doubt any historical value of the Muslim sources.8 Adding to the problem is that Islamic history was not only written more than a century after the accounts it purports to record, but that it was later rewritten under the Addassid caliphate “dictated by a host of sectarian and political considerations”.9 Robert Hoyland recognizes the problematic nature of the literary Muslim source material admitting that,

Islamicists, who once rejoiced that their subject “was born in the full light of history,” have recently been discovering just how much apparent history is religio-legal polemic in disguise, some even doubting whether the host of Arabic historical works that appear in the late eighth and early ninth centuries contain any genuine recollection of the rise and early growth of Islam.10

On the other hand, Asma Afsaruddin argues in The First Muslims, History and Memory that some kernel of truth must exist in the Muslim sources contending that “the narratives . . . as late as the second or third centuries of Islam . . . must have existed contemporaneously with the earliest Muslims.”11 The 1977 analysis of Patricia Crone and Michael Cook on early Islam is “based on the intensive use of a small number of contemporary non-Muslim sources the testimony of which has hitherto been disregarded”.12

What were the dynamics of early Islam? To answer that question we must first understand the context in which Islam arose and attempt to uncover pre-Islamic Arabia from historical sources. I shall argue that early Islam was primarily a struggle for political power and tribal dominance, and not a religious proclamation. The fate of Muhammad and his immediate first four successors, of which only one died of natural causes, indicate a far greater struggle for political power than the noble proclamation of a new faith. I shall consider the objection that Islam was first-and-foremost a religious proclamation and show that the historical evidence does not support that theory; in fact early non-Muslims who acknowledged that Islam indeed had some kind religious perspective tended to regard early Islam as an aberrant offshoot of heretical Christianity rather than a new religion.

Pre-Islamic Arabia

To understand the perspective of non-Muslims regarding the rise of Islam in the seventh century, one must first grasp pre-Islamic Arabia. Arabian geography occupied a somewhat central position between great world empires. But once again, sources attesting to pre-Islamic Arabia are scarce; Hoyland notes that “the would-be student of Arabian history is confronted with a Herculean task. Greo-Roman authors penned a number of treatises on Arabia and matters Arab, but these are all now lost except for a few fragments and scattered citations by later writers”.13 He admits that our knowledge of Arabian history “rests on meager foundations”.14

Tribal allegiance was foundational to pre-Islamic Arabian culture and is still essential for modern Arabs. Tribes, rather than states or empires, were the dominant political forces in per-Islamic Arabia.15 Louis Hamada traces the ascent of semitic Arabs; they were originally nomadic tribes wandering in the wilderness.16 According to some, pre-Islamic Arabia consisted largely of nomadic Bedouin tribes who hunted, served as bodyguards, escorted caravans, worked as mercenaries, and traded or raided to gain animals, women, gold, fabric, and other luxury items; in addition with Arabs living within settlements.17

The polytheistic Bedouin clans placed heavy emphasis on kin-related groups, with each clan clustered under tribes. The immediate family shared one tent and can also be called a clan. Many of these tents and their associated familial relations comprised a tribe. Although clans were made up of family members, a tribe might take in a non-related member and give them familial status. Society was patriarchal, with inheritance through the male lines. Tribes provided a means of protection for its members; death to one clan member meant brutal retaliation.18

Others such as Ilkka Lindstedt and Fred Donner argue that it is unlikely that nomadic people have ever formed more than a small fraction of its population . . . Most Arabians, then, are, and have been, settled people”.19 Phil Parshall who was a missionary among Muslims for more than twenty years observes in his outreach book Beyond The Mosque, Christians Within Muslim Community that Arabia has historically “been so constituted as to form a number of tribes, very loosely held together by loyalty to a particular leader or by belief in the group’s descent from a common ancestor”.20 David Waines argues that the pre-Islamic “pagan Arab bowed first to the force of oral tribal tradition (sunnah) rather than to the power of the gods”.21 Waines comments on the importance of tribal relations in pre-Islamic Arabia noting that “Correct conduct was measured by conforming to the ways of the ancestors, and the upholding of tribal honor”.22 Reflecting on the importance of tribal affiliation, he continues, “without a tribe one had no name and was a virtual non-being.”23 The 8th century Muslim historian Ibn Ishaq records that Muhammad “offered himself to the tribes of the Arabs at the fairs whenever opportunity came”.24 In fact, tribal affiliation and allegiance was central to life in pre-Islamic Arabia for both nomads and the settled people, and is still very significant in modern Saudi Arabia.25

Beatrice Leal insightfully observes that “the region was not unified as a single country; rather there were many different Arab tribes and kingdoms”.26 In her essay, she offers an overview of the kingdoms making up pre-Islamic Arabia. Explaining the veneration of the Black Stone in the Ka’ba of Mecca, she presents a “widespread religious practice in Arabia, going back into the first millennium B.C.E., was the veneration of selected stones”; referencing multiple pagan gods she notes the co-existence of Judaism, Christianity, and to a lesser extent Zoroastrianism. 27 We can conclude that pre-Islamic Arabia consisted of polytheistic Bedouin tribes with multiple communities of co-existing Jews, Christians, and to a lesser extent those who practiced Zoroastrianism. It would fall to Muhammad to ultimately initiate a concerted forced movement to unify the Arabic tribes. Up until about the fourth century, almost all inhabitants of Arabia were polytheists, while in the fourth to sixth centuries Christianity made major inroads into Arabia.28 Towards the sixth century, among the settled Arabs was an increasing conversion to Christianity to “facilitate their integration with the urban population.”29

A key question that must be addressed is whether there was a propensity for violence and tribal warfare in pre-Islamic Arabia. Marco Demichelis argues that “the Arab conquests which started in the third decade of the seventh century were far from being ‘Islamic’”.30 His thesis is that early conflict existed in Arabia before Islam appeared on the scene. After 545 (some 25 years before Muhammad was born) when the Romans and Persians had achieved a truce in Arabia, the Arabs continued to fight each other.31 It is interesting to note that victory in conflict between the various tribes in pre-Islamic Arabia involved “the exaction of tribute and protection money”.32 In fact, tribute and protection money were later to become defining attributes of early Islam.

Early Views Of Islam

Ayman Ibrahim notes, “For the most part, non-Muslims did not view Muhammad favorably”.33 An indication of the wariness that pre-Islamic Arabians exhibited towards Muhammad is reflected in the fact after twelve years of proclaiming his message in Mecca, he left for Medina, forced out of Mecca with only a small group of followers.

The Doctrina Jacobi is an ancient Greek tract that apparently provides one of the earliest external accounts of Islam; it presents a significantly different picture of Islam than found in traditional Muslim sources. Reference is made to an unnamed prophet among the Saracens (a term the Romans used to refer to people of Arabia) as “an imposter. Do the prophets come with sword and chariot? . . . There is no truth to be found in the so-called prophet, only bloodshed; for he says he has the keys of paradise, which is incredible”.34 While the text does not refer to Muhammad by name, the time period matches that of Muhammad in Arabia leaving one to wonder if “there was any more famous prophet with a sword during Muhammad’s time”.35 A contemporary sermon lists the atrocities of the Saracens as “the burning of churches, the destruction of monasteries, the profanation of crosses snd horrific blasphemies against Christ and the church”.36 In addition, the early writers and compilers of Muslim tradition “seem to have been obsessed with the question of the distribution of booty after a city or area had been conquered”.37 It seems there may have been more worldly reasons for Islamic expansion than the proclamation of a new faith, namely a lust for the spoils of war.

Recognizing the importance of tribal affiliation and relationships, Kennedy argues that early Muslim leadership “set out to destroy or at least reduce the loyalty to the tribe”; in his view the Muslim community (umma) was to be a new sort of tribe based not on descent but commitment to the umma.38 The umma would now provide the protection and security previously accessible by their tribe. However, he also acknowledges that dismantling strong tribal loyalty was not easy; when it came to the “struggle for resources, for salaries and booty, tribal rivalries acquired a fierce and brutal intensity”.39 Such attitudes and behavior don’t seem compatible with a community allegedly formed around a new faith; rather they reveal true motives.

Forced out of Mecca, Muhammad from the prestigious tribe of Quraysh, was invited to Medina in 622 to mediate the inter-tribal feuding and rivalries that infecting the city. Muhammad was seen as a warrior as well as prophet and judge, and the Islamic community began expansion through conflict as well as preaching.40

Early Islam Was A Thrust For Political Power

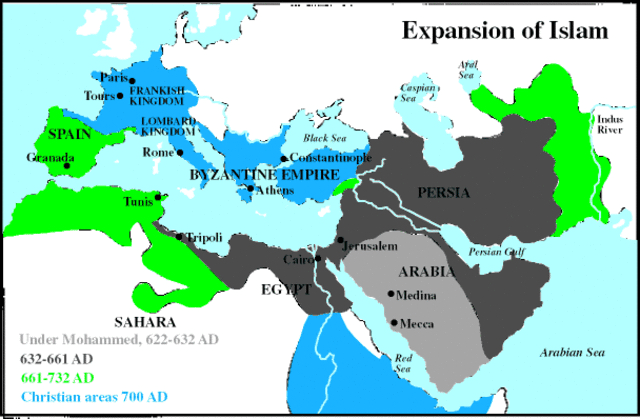

By the end of his life, the political influence of Muhammad was such that delegations arrived from tribes all over the peninsula “accepting his lordship and agreeing to pay some form of tribute”.41 The forced payment of tribute does not accord well with the Muslim historical view of the proclamation of a new faith. Figure 1 depicts the remarkable and rapid geographical expansion of Islam.

Expansion Of Islam

Figure 1

Islams’s advent entails not only the emergence of a new faith but also “the unification of the Arabic-speaking tribes and the rise of the idea that they all make up one people”.42 By the end of the Rashidun caliphate, the entire Arabian peninsula was under Islamic control. This implies a non-religious predominate theme of the exercise of political power. Bernard Palmer argues that . . .

Contrary to the spread of Christianity, which has been carried our largely through peaceful means (although we have our share of bloodthirsty eras that bring shame to our cheeks), the burgeoning spread of Islam has been carried out chiefly on the battlefield. Peoples have embraced Islam, but usually only after the Muslims have driven them to their knees.43

In his peer-reviewed article, graduate student Caleb Strom comments on the first thirty years of Islam, “The thirty years during when they ruled were filled with political intrigue, corruption, assassination, and civil war but also impressive military conquests and the formation of the major divisions that define Islam today”.44 Despite the unification of the Arabs that Islam ultimately achieved, the thirst for political power never subsided as reflected in the “inter-clanic conflict which emerged after the Prophet’s death”.45 The Islamic propensity for political power continues and is not restricted to inter-tribal conflict. The historian Bernard Lewis (Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University with an expertise in the history of Islam) reminds us that “We tend nowadays to forget that for approximately a thousand years, from the advent of Islam in the seventh century, until the second siege of Vienna in 1683, Christian Europe was under constant threat from Islam”; he points out that most of the new Muslim domains were wrested from Christendom including Syria, Palestine, Egypt and North Africa.46 Even to this day, brutal military conflict still occurs within Islam as evidenced by the Iran/Iraq war from 1980 until 1988 that Iraq initiated as a conflict between Sunni and Shia Muslims. The estimated total casualties range from 1,000,000 to twice that number; the number killed on both sides was perhaps 500,000.47

In his exposition on the centrality and importance of the mosque in Islam, Waines notes that the Friday sermon traditionally “had a political touch” and that the mosque served also for the “conduct of government business”.48 Hoyland argues that “Muhammad played a much more crucial role in the uprising that followed his death, and his politico-religious message and organization were key to the future direction of the conquests” (emphasis mine).49 Hoyland’s choice of the phrase “politico-religious” is telling, indicating that Muhammad’s message was a primarily political one that was couched in religious terms. In his introduciton, Hoyland argues that “Religion is integral to the conquests and the evolution of an Islamic empire, but religion is not just piety and devotion, especially not in the seventh century; it is as much about power and identity”.50

A never-ending struggle for political power seems to be in the Islamic DNA beginning with the earliest days of Islam under Muhammad and continuing today.

The Fate Of Muhammad And the Rashidun Caliphate

There is perhaps no more powerful evidence that early Islam was primarily a struggle for power than the fate of Muhammad and his immediate four successors, known as the Rashidun (“rightly guided”) caliphate. Only one of these five individuals died of natural causes. Muslim traditions are in general agreement that Muhammad was poisoned and died in 632; Sunni Muslims believe he was poisoned by a Jewish woman while Shiite Muslims believe that he was killed by two of his wives.51 Muhammad’s immediate successor, Abu Bakr, was the first caliph and the only one to die of natural causes in 634. The second caliph, Umar, was assassinated in 644.52 The third caliph, Uthman, was murdered by Muslim rebels in 656.53 The fourth caliph, Ali, was assassinated in 661.54 Most of the significant expansion of the Islamic empire occurred during this period of the Rashidun caliphate. Within the first thirty years of Islam, four of the five leaders met violent deaths in a struggle for power during a rapid expansion of their empire that was primarily political.55

An Aberrant Offshoot Of Christianity

It is clear that Muhammad had significant exposure to Judaism and Christianity and incorporated multiple elements from those faiths into his new belief system. The angel that appears to him to reveal the Qur’an is Gabriel, known to us only from the Old Testament (book of Daniel) and New Testament (book of Luke.) In fact, there are references to dozens of Biblical persons and events in the Qur’an to include Adam, Noah, Abraham, Lot with Sodom and Gomorrah, Joseph, Moses, David, Mary, Jesus, John the Baptist. Timothy Tennent, President of Asbury Theological Seminary observes that, “The emergence of Islam and the Qur’an can be properly understood only within the larger context of the Bible and the monotheism of Islam’s two main predecessors, Judaism and Christianity. The dozens of superficial similarities between the Qur’an and the Bible are striking”.56 There are more than a dozen references to Jesus in the Qur’an scattered across fifteen different surahs. Arabia was surrounded by Christian countries and civilizations, and there were Arab Christian tribes and settled communities within Arabia that Muslims had regular contact with.57 While there are multiple affinities of Islam with the Bible, there are sufficient essential differences to characterize it as both aberrant and a heresy (i.e., the rejection of the divinity of Jesus Christ, its position on the crucifixion, a rejection of the imago dei, a denial of salvation by grace alone, a rejection of the resurrection of Christ, etc.). Ohlig asserts that “it was not until relatively late in the 8th, or even as recently as the early 9th century, that the idea arose that the Arabic movement was a new and no longer Christian religion” (original emphasis by the author).58

There is the legendary story of Muhammad’s encounter with the monk Sergius, nicknamed Bahira by the Arabs, who had travelled to the “wilderness of the sons of Ishmael”.59 The Arabic and Syriac redactions recount Bahira’s meeting with Muhammad in 581, foretelling his prophethood and leading out of paganism into monotheism.60 If there is a kernel of truth to this story, it may mark Muhammad’s conversion from paganism to monotheism. There is an Islamic tradition that mentions a “monk exiled for false belief” in whom Muhammad’s wife confided her anxiety in 610 over her husbands visions who is identified as “Waraqa ibn Nawfal, al alleged Arab convert to Christianity and whom identifies Muhammad as the long-awaited prophet.61 Hoyland points out that Waraqa seems to share traits with Bahira who was exiled from Byzantine lands for heresy. From the perspective of Christianity, both Bahira and Waraqa seem to heretics.

In the early eighth century, Christian theological polemics against Islam began to appear, including the famous tract by John of Damascus, himself a former Umayyad administrator before retirement to a monastery.62 He wrote, “Muhammad, the founder of Islam, is a false prophet who, by chance, came across the Old and New Testament and who, also, pretended that he encountered an Arian monk and thus devised his own heresy”.63

Conclusion

Uncovering the historical details of early Islam with any certainty is challenging at best and impossible at worst. However, even the Muslim sources that were written—and then rewritten more than two centuries later—paint a vivid picture of the dynamics at work in early Islam. Islam was born into a culture characterized by strong tribal allegiance and affiliation. They early sources portray a movement motivated primarily by a lust for political power and infighting. The earliest records of non-Muslims depict an unflattering picture while the earliest Islamic traditions portray an obsession over the division of the spoils of war from conquered areas. The forced extraction of tribute is difficult to reconcile with the proclamation of a new religious faith. There is no doubt that Muhammad was exposed to Judaism and Christianity with the dozens of superficial similarities between the Qur’an and Bible; he incorporated some of their elements into his belief system. Either he misunderstood or manipulated what he was exposed to, or was (more likely) exposed to heretical Christianity. The fate of Muhammad and his immediate four successors in the Rashidun caliphate, only one of whom died from natural causes, is powerful evidence of the infighting for political power and leadership among different clans of the Quraysh tribe. The dynamics of early Islam were a strong leader who was not afraid to use force to accomplish his ends, and who incorporated (most likely) heretical Christian theology into a new faith system for the primary purpose of consolidating his political power and building an empire.

1Hugh Kennedy, The Great Arab Conquests: How The Spread Of Islam Changed The World We Live In, Da Capo Press, 2007, 1, Kindle

2David Aikman, Foreword to The Last of the Giants by George Otis Jr, Tarrytown, New York, Chosen Books, 199, 17

3David Waines, An Introduction to Islam, Second Edition, Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 2003, 156, Kindle

4Karl-Heinz Ohlig (editor), The Hidden Origins of Islam, Lanham, MD, Prometheus Books, 2010, 8

5Karl-Heinz Ohlig (editor), Early Islam, A Critical Reconstruction Based On Contemporary Sources, Lanham, MD, Prometheus Books, 2013, 10

6Ohlig, editor, Early Islam, 10

7Gabriel Said Reynolds, The Emergence Of Islam, Classical Traditions In Contemporary Perspective, Minneapolis, MN, Fortress Press, 356, Kindle

8Herbert Berg (editor), Routledge Handbook On Early Islam, New York, Routledge, 2018, 1, Kindle

9Ayman S. Ibrahim, Conversion To Islam, Competing Themes In Early Islamic Historiography, New York, Oxford University Press, 2021 23, Kindle

10Robert G. Hoyland, Seeing Islam As Other Saw It, A survey And Evaluation of Christian, Jewish, And Zoroastrian Writings On Early Islam, Princeton, New Jersey, Darwin Press, 1997, 404, Kindle

11Asma Afsaruddin, The First Muslims, History and Memory, Oxford, England: Oneworld Publications, 2007, Introduction, XVII

12Patricia Crone & Michal Cook, Hagarism, The Making Of The Islamic World, Cambridge, London: Cambridge University Press, 1977, 18, Kindle

13Robert G. Hoyland, Arabia And The Arabs, From The Bronze Age to the coming of Islam, London: Routledge, 2002, 1, kindle

14Hoyland, Arabia And The Arabs, 9, Kindle

15Kennedy, The Great Arab Conquests, 37, Kindle

16Louis Bahjat Hamada, Understanding The Arab World, Nashville, Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1990, 41

17Hoyland, Arabia And The Arabs, 236, Kindle

18https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-hccc-worldcivilization/chapter/the-nomadic-tribes-of-arabia/

19Ilkka Lindstedt, Berg (editor), Routledge Handbook On Early Islam, 162, Kindle

20Phil Parshall, Beyond The Mosque, Christians Within Muslim Community, Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1985, 23

21Waines, An Introduction to Islam, 10, Kindle

22Waines, An Introduction to Islam, 10, Kindle

23Waines, An Introduction to Islam, 10, Kindle

24F. E. Peters, A Reader On Classical Islam, Princeton NJ, Princeton University Press, 1994, 68, Kindle

25https://sauditimes.org/2020/10/22/tribes-saudi-arabia/; https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/tribes-and-tribalism-arabian-peninsula

26Beatrice Leal, Pre-Islamic Arabia, an overview, https://smarthistory.org/pre-islamic-arabia/

27Leal, Pre-Islamic Arabia, https://smarthistory.org/pre-islamic-arabia/

28Hoyland, Arabia And The Arabs, 139-147, Kindle

29Hoyland, Arabia And The Arabs, 237, Kindle

30Marco Demichelis, Violence in Early Islam, Religious Narratives, the Arab Conquests and the Canonization of Jihad, London, I.B. Tauris, 2021, 31, Kindle

31Demichelis, Violence in Early Islam, 39, Kindle

32Hoyland, Arabia And The Arabs, 240, Kindle

33Ayman S. Ibrahim, A Concise Guide to the Life of Muhammad, Answering Thirty Key Questions, Grand Raids, MI: Baker Academic. 2022, 109, Kindle

34Crone & Cook, Hagarism, The Making Of The Islamic World, 71-77, Kindle

35Ibrahim, A Concise Guide to the Life of Muhammad, 110, Kindle

36Crone & Cook, Hagarism, The Making Of The Islamic World, 123, Kindle

37Kennedy, The Great Arab Conquests, 20, Kindle

38Kennedy, The Great Arab Conquests, 38, Kindle

39Kennedy, The Great Arab Conquests, 39, Kindle

40Kennedy, The Great Arab Conquests, 46, Kindle

41Kennedy, The Great Arab Conquests, 46, Kindle

42Reynolds, The Emergence Of Islam, 312, Kindle

43Bernard Palmer, Understanding The Islamic Explosion, Alberta, Canada: Horizon House Publishers, 1980, 37

44Caleb Strom, https://www.ancient-origins.net/history-important-events/first-caliphs-0011569

45Demichelis, Violence in Early Islam, 256, Kindle

46Raymond Ibrahim, Sword And Scimitar, New York: Da Capo Press, 2018, xiii, Kindle

47https://www.britannica.com/event/Iran-Iraq-War

48Waines, An Introduction to Islam, 197, Kindle

49Robert G. Hoyland, In God’s Path, The Arab Conquests And The Creation Of An Islamic Empire, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2015, 1098, Kindle

50Hoyland, In God’s Path, 158, Kindle

51Ibrahim, A Concise Guide to the Life of Muhammad, chapter 18, Kindle

52Ibrahim, Sword And Scimitar, 34, Kindle

53Demichelis, Violence in Early Islam, 86, Kindle

54Demichelis, Violence in Early Islam, 120, Kindle

55Strom, https://www.ancient-origins.net/history-important-events/first-caliphs-0011569

56Timothy C. Tennent, The Bible and Islam, ESV Study Bible, Wheaton, IL, Crossway Bibles, 2008, 2629

57M. J. Nazir-Ali, Islam And Christianity, New Dictionary Of Theology (Sinclair B. Ferguson, David F. Wright, J I. Packer, editors), Downers Grove, IL, InterVarsity Press, 1988, 343

58Ohlig (editor), Early Islam, 2013, 271

59Hoyland, Seeing Islam As Other Saw It, 7237, Kindle

60Ibrahim, A Concise Guide to the Life of Muhammad, xi, Kindle

61Hoyland, Seeing Islam As Other Saw It, 12530, Kindle

62Levy-Rubin, Routledge Handbook On Early Islam, 188, Kindle

63Reynolds, The Emergence Of Islam, 3251, Kindle

Leave a comment